I don't remember when I first saw him. If I were pressed to put a date on it, it was in the autumn of 2008 and I was in Connecticut on an artist residency. He just floated into the painting unannounced, drifting laterally, from the left edge, slowly sinking down towards the bottom of the picture plane.

My temporary studio was in an old farmhouse and I was in the good company of artists, writers, and musicians from across the globe. I don't remember what I proposed to do in Connecticut, but the initial idea never materialized. This is not unusual during residencies, and generally forgiven by the host. Plans and intentions are often dropped at the threshold of new imaginings.

I walked into the studio, slid open the expansive double doors to the creek-side forest, and sat down at the drafting table. A hummingbird flew in, stopping to hover just beyond the tip of my nose. It was too close to focus, so I closed my eyes and listened to the hum, while the apparent wind of the wingbeats ruffled my eyebrows. Then it was gone.

This event triggered thoughts about flight, about my new colleagues from distant lands, about people in the air. The vulnerabilities and freedoms associated with leaving the earth.

Children jumping, tight rope walkers, astronauts, women falling, aerialists, pilots, and one lone person with a parachute.

It was as if the newspapers and magazines were suddenly filled with images of people falling, jumping, and floating, page after page. I clipped out the pictures, taped them to the light table and traced each one. There were people in the sky, and it was my job to draw them.

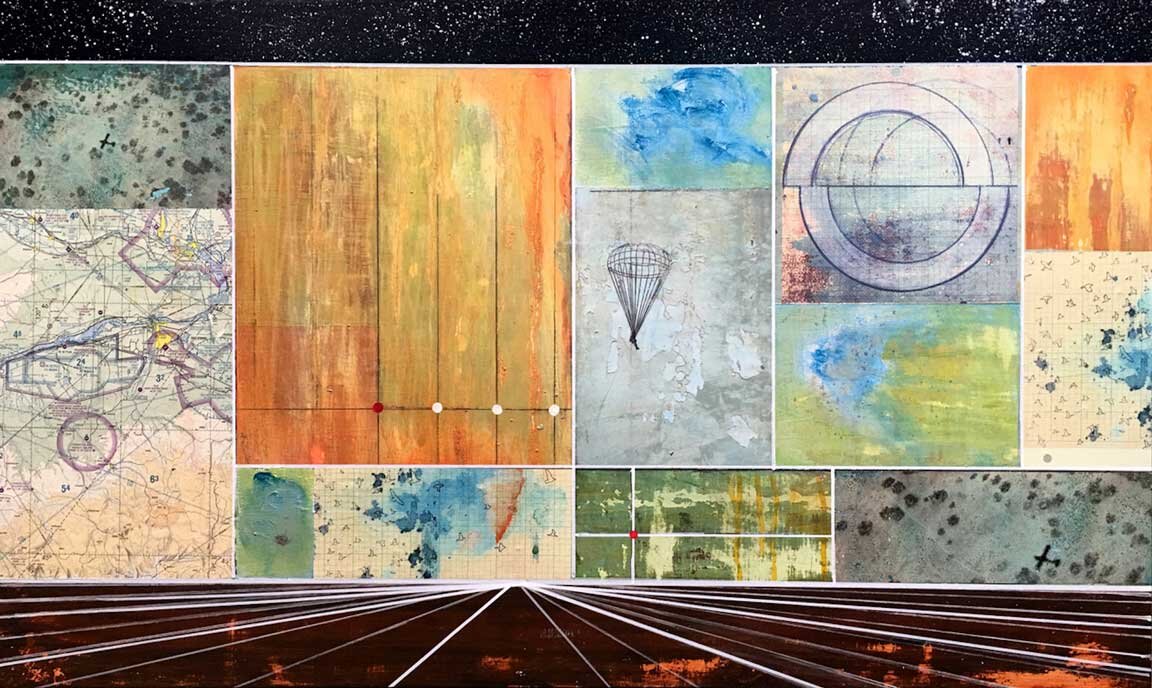

Airlift - 2008

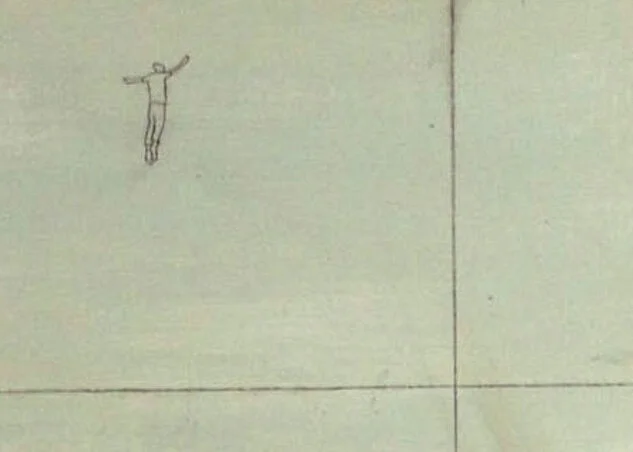

The "people in the sky" series didn't last long. What goes up must come down, I guess. Most of my subjects ended up crumpled in a waste bin in Connecticut, but one did made the trip out West. Tucked in my sketchbook between two gridded pages was a graphite drawing of a paratrooper, seemingly suspended, with no horizon or ground plane for context. I gendered the paratrooper a "he," judging from the size of the boots.

The image is a simple silhouette, but not without details. A close look can discern a sort of pith helmet, big, baggy pants tucked in at the ankle, and a pack on the back of the figure, with strings radiating skyward, to a billowing, inflated, bunch of fabric above.

Whispering Pines - 2014

For eleven years, this paratrooper floated through my paintings. Sometimes, the placement was intentional, but mostly, he just seemed to come of out of nowhere. I would be pushing paint around, working out some details of landscape and realize there was a blank spot in the composition. Enter, the paratrooper. I would trace the original newspaper clipping, flip it over, add glue, and paste him into the landscape. Dozens of times over.

Mexicali - 2016

Though many asked why I was drawing this figure, I really had no answer and I, myself, didn't need one. There was just something I liked about the idea that a paratrooper, or anyone, really, could float through my painting. As if the painting itself were a roadside attraction or scene in a movie, and you could just drift on by.

The only thing unusual was how long the paratrooper stuck around. He floated through, maybe, twenty different paintings, over a twelve-year period of time. The paintings sold well. Different iterations of the paratrooper are now suspended over side boards, couches, mantles, and desks in homes and offices across America. It must be hard to steer a parachute. When a work sold, I imagined that each transaction helped him to reach a new destination.

Double Creek - 2018

In 2016, my husband, Craig, and I moved to the Methow Valley. We were finally calling "home" a place we had both loved for years. The house purchase happened quickly. We met a pilot at a concert and he and Craig started talking airplanes. Craig mentioned that we were looking for a house, and our new pilot friend said "I've got the place for you." It felt really impulsive, but we just trusted our guts and went with it, buying a house and ten acres from some friends of the pilot, over a cup of tea.

We moved in on Craig's birthday, sleeping on the floor in what would be the living room. I woke up early and stepped outside in the soft morning light and crisp mountain air. I looked to the west. I blinked and looked again. For reasons I could not imagine, the sky was filled with people in parachutes. Maybe six or so, slowly floating down to earth. I could hear their conversations, as they drifted and descended. Helmets on, big boots, packs on their backs, and a circle of billowing fabric over each individual, just like the ones I'd been drawing for years.

My parachutist was real, and not only that, he had friends! Tears streamed down my cheeks. I liked the house and the land and the views, but had no idea that our new place was across the street from the North Cascades Smokejumper Base. It was pure fortune that we moved in during the month of May, when the rookies arrive and practice their delicate and dangerous business of parachuting into forest fires.

My mind raced. Did the right side of my brain somehow predict this? Was it fate? Was marrying my husband and moving to the Methow Valley the culmination of a journey that began in Connecticut, twelve years ago? I didn't need to know the answer, but somehow, this painting had become real and I was standing in the middle of it, barefoot in the morning, with parachutists circling over my head and mountains in the background.